If you are staying in one of these countries, you might be working too much!

This article covers:

- Countries with relatively longer working hours

- Countries with relatively shorter working hours

- How OECD calculates work hours?

- Why the disparity in working hours within the OECD?

- What about countries outside the OECD?

- Why do lower & middle-income countries log in more hours?

- Final Thoughts

- Sending money overseas?

“On average, people now spend approximately 13 years and two months of their lives at work.”

– 2017 article in the Huffington Post

“Most of the world’s population (58%) spends one-third of their adult life at work contributing actively to the development and well-being of themselves, their families and of society.”

– Article on the website of the World Health Organization

These are just TWO of the millions of results we got in response to a Web search for the term ‘how much time do we spend at work?’

On a ‘macro’ level, the relationship between employment and economic growth may be a highly-debated issue among economists and policy-makers but it is also true that the former affects the latter in complex, multi-dimensional ways that just cannot be ignored.

So, regardless of nationality, gender, religion or socio-economic status, the world of work matters to everyone.

However, not everyone agrees on ‘how much’ work matters. The number of hours a day a person devotes to their work differs from one country to another. To put this in another way, some countries have ‘long’ working hours while others have ‘short’ working hours.

Consider this example:

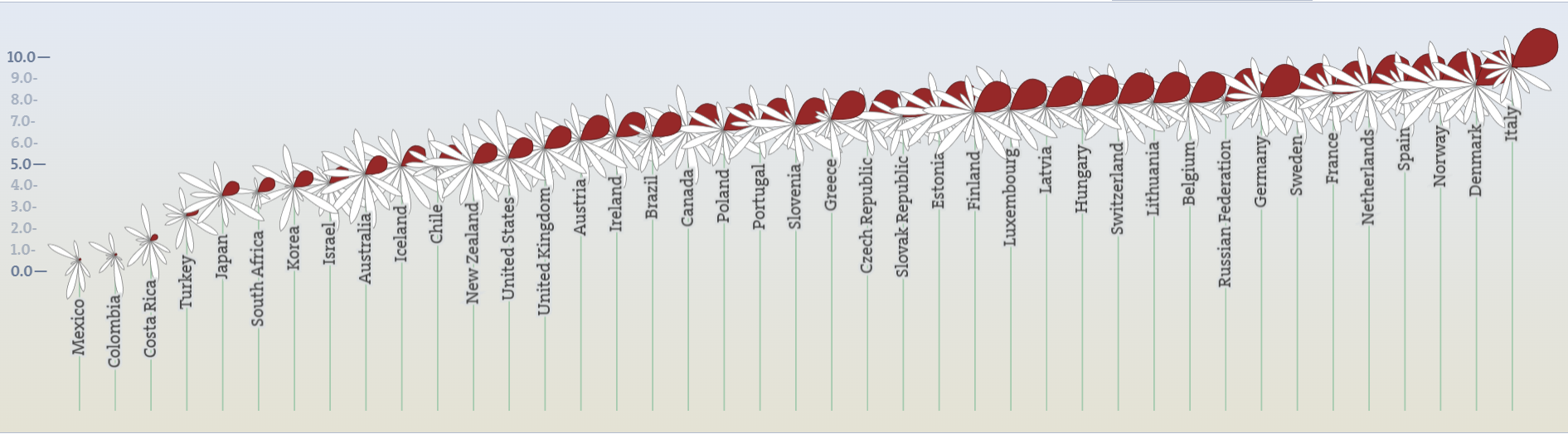

A 2020 report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), whose 36 members include many of the world’s most advanced countries (USA, UK, Australia, Germany, etc) but also some rapidly developing and emerging nations (Chile, Turkey, Mexico, etc) found that in terms of hours worked, in 2020 Mexico had the longest work days, while Germany had the shortest.

But what do these words – long and short – really mean? The only way to understand the meaning of ‘long’ versus ‘short’ is to remember that these definitions are relative. In other words, a 40-45 hour (or even more) average work week by country may be considered ‘short’ in one country but it may be frowned upon and considered too ‘long’ in another country.

To have a better idea, let’s deep dive into the context:

Countries with relatively longer working hours

Wondering what country works the most hours? Before we discussed this, let’s understand the definition.

Going by this definition of ‘average annual hours worked in terms of hours/worker/year:

In 2021, the average working hours Mexicans spent was a little over 2,128 hours at work per year. This is the equivalent of over 41 hours per week (assuming he works all 52 weeks of the year).

In contrast, the average working hours German spent only 1,349 hours at work in a year, an equivalent of a 26-hour work week.

In 2021, the OECD annual average was 1,716 hours/worker. This equates to 33 hours/worker/week.

All OECD countries where the average work week by country is longer than are:

Country | Hours/worker | Hours/worker/week(52 weeks/year) |

Mexico | 2,128 | 41 |

Costa Rica | 2,073 | 46 |

Colombia | 1,964 | 38 |

Chile | 1,916 | 37 |

Korea | 1,910 | 37 |

Malta | 1,882 | 36 |

Russia | 1,874 | 36 |

Greece | 1,872 | 36 |

Romania | 1,838 | 35 |

Croatia | 1,835 | 35 |

Poland | 1,830 | 35 |

United States | 1,791 | 34 |

Ireland | 1,775 | 34 |

Estonia | 1,767 | 34 |

Czech Republic | 1,753 | 34 |

Israel | 1,753 | 34 |

Cyprus | 1,745 | 34 |

New Zealand | 1,730 | 33 |

OECD Average | 1,716 | 33 |

In Europe, the Polish put in the most hours at work, but their work weeks are still almost 5 hours – roughly a full work day – shorter than the work weeks of Mexican workers.

Workers in the United States, Estonia, Czech Republic, Cyprus and Israel enjoy shorter work weeks than 11 other countries in the OECD, but they still work slightly longer than the OECD average of 33 hours per week.

You might also want to read: 200 + Countries And Only 14 Ways To Charge your Phone Globally

Countries with relatively shorter working hours

These are average working hours by country (from longest hours to shortest):

Country | Hours/worker | Hours/worker/week(52 weeks/year) |

Hungary | 1697 | 33 |

Australia | 1694 | 33 |

Canada | 1685 | 32 |

Italy | 1669 | 32 |

Portugal | 1649 | 32 |

Spain | 1641 | 32 |

Lithuania | 1620 | 31 |

Bulgaria | 1619 | 31 |

Japan | 1607 | 31 |

Latvia | 1601 | 31 |

Slovenia | 1596 | 31 |

Slovak | 1583 | 30 |

Switzerland | 1533 | 29 |

Finland | 1518 | 29 |

United Kingdom | 1497 | 29 |

Belgium | 1493 | 29 |

France | 1490 | 29 |

Sweden | 1444 | 28 |

Austria | 1442 | 28 |

Iceland | 1433 | 28 |

Norway | 1427 | 27 |

Netherlands | 1417 | 27 |

Luxembourg | 1382 | 27 |

Denmark | 1363 | 26 |

Germany | 1349 | 26 |

In an average work year, German workers put in a whopping 1349 hours (the equivalent of 15 weeks) less than their counterparts in Mexico. Like Germany, workers in Netherlands and 4 of the highly-developed Nordic countries of Iceland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden also enjoy short work weeks of 26 to 28 hours.

You Might Also Want To Read: Retiring abroad: 6 crucial factors to consider before moving overseas

How OECD calculates work hours?

According to the OECD, the number of hours worked per person in a given country is defined by the following formula:

- Average annual hours worked = Total number of hours actually worked per year

- (Hours per worker per year) The average number of people in employment per year

This definition determines which countries have long working hours and which ones have shorter working hours. This is also how OECD determined that Mexico had the longest workdays among all the countries in the OECD group in 2021.

The OECD data covers both employed and self-employed workers.

What makes up annual working hours?

- Regular work hours of full-time, part-time and part-year workers

- Paid and unpaid overtime

- Hours worked in additional jobs

What Doesn’t Make UP Annual Working Hours?

- Public holidays, strike, labour dispute or bad weather

- Annual paid leave

- Time off due to illness, injury or temporary disability

- Maternity leave

- Parental leave

- Sabbaticals for schooling or additional training

- Slack work for technical or economic reasons

- Compensation leave, etc

You Might Also Want To Read: 5 ways to make friends & meet people while working abroad

Why the disparity in working hours within the OECD?

Socio-economic, historical and cultural factors play an important role in determining the average working hours by country.

In Mexico, long-standing fears about unemployment, rising inflation and slowing economic growth mean people work longer hours per week. At the other end of the spectrum, German workers put in fewer hours at work and enjoy a better work-life balance thanks to a culture that gives importance to leisure as well as work.

Also, because they live in an advanced, highly industrialised economy – Europe’s largest and strongest – they don’t feel the same desperation to work longer hours to increase their income.

Despite the shorter working hours, however, German workers are among the most productive in the world, ahead of workers in the, France and even Finland.

Workers in the rich European countries of Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Iceland also work fewer than 1,500 hours per year on average, over 200 hours (approximately 5.5 weeks) fewer hours than the OECD average.

According to the OECD 2020 Better Life Report, workers in Italy enjoy the best work-life balance in the world. In addition, the percentage of Italian employees who regularly work ‘very long hours’ has steadily declined since 2008 to only 3.3%, compared to the overall OECD average of 10%.

In 2020, the developed nation with the longest working hours was South Korea. In fact, weekly working hours in this country were longer than in any other OECD country except Mexico and Costa Rica, mainly due to official efforts to boost economic growth. However, long work hours have also fuelled concerns about social problems such as falling birth rates and slowing productivity.

To address these concerns and change societal attitudes towards work, South Korea’s National Assembly passed a law in March 2018 to slash working hours (capping the maximum allowed from 68 hours/week to 52 hours/week) and give its workers the ‘right to rest’.

This may be why the average annual hours worked by South Korean workers fell from 1,993 hours in 2018 to 1,967 hours in 2019 and finally to 1,908 hours in 2017.

Japan, another developed country in the OECD, has for years been associated with a workaholic culture that spawned the term karoshi (death by overwork). Japan’s culture of working long hours was formed during the boom times of the 1960s-1990s when people who worked overtime were valued and therefore enjoyed greater career success.

However, the rising number of karoshi cases has fuelled a demand for reforming labour laws, improving working conditions and of course reducing the work hours across the Japanese workforce. This may be why the OECD report found that in 2020, the average Japanese worker worked only about 1,598 hours per year (a 31-hour work week), a figure that is below the OECD average of 1,687 hours. The 2020 figure is the lowest for Japan in 4 years, falling from 1,709 in 2017 to 1,680 in 2018 and 1,644 in 2019.

What about countries outside the OECD?

The OECD is a group of only 38 out of the almost 200 countries in the world today. Therefore, OECD’s report does not provide any information about the working hours in non-OECD countries.

A 2022 World Employment Social Outlook study by the International Labour Organization (ILO) showed that lower and middle-income countries tend to work longer hours than their richer, more developed counterparts.

Why do lower & middle-income countries log in more hours?

- Lower wages

- Lower standard of living

- Job insecurity

- Larger families

- Socio-cultural attitudes

- Historical precedents

The data from ILO also showed that in Asia, more people work the longest hours. Many countries have no universal national limit for maximum weekly working hours and some have thresholds as high as 60 weekly hours or more in most developed countries.

The ILO’s international labour standards on working time have been in place since 1919 and have set the maximum threshold of 48 hours for the working week. Many countries such as India also do not have a legally-guaranteed minimum amount of annual leave, a factor that affects the average annual hours worked by people in the workforce.

According to a 2022 analysis of the most overworked cities, workers in several Asian cities were found working longer hours.

Asian Cities To Feature In The Top 10:

#2: Hong Kong (China)

#3: Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia)

#4: Singapore

#6: Tokyo (Japan)

#7: Bangkok (Thailand)

Bangkok also holds the dubious distinction of being the world’s stingiest city with regards to annual leave offered to its workers: 6 days/year, compared to the global average of 23 days.

The ILO report also found that countries like Malta, Bhutan and Bangladesh have 50% of the workers working 49 or more hours per week.

These figures are in stark contrast to Europe, where most countries have legally stipulated that weekly working hours be capped at 48 hours. In some European countries such as Belgium, although the legal working week is capped at 38 hours, companies are allowed to alter working hours in line with their particular requirements, as long as workers are appropriately remunerated for overtime.

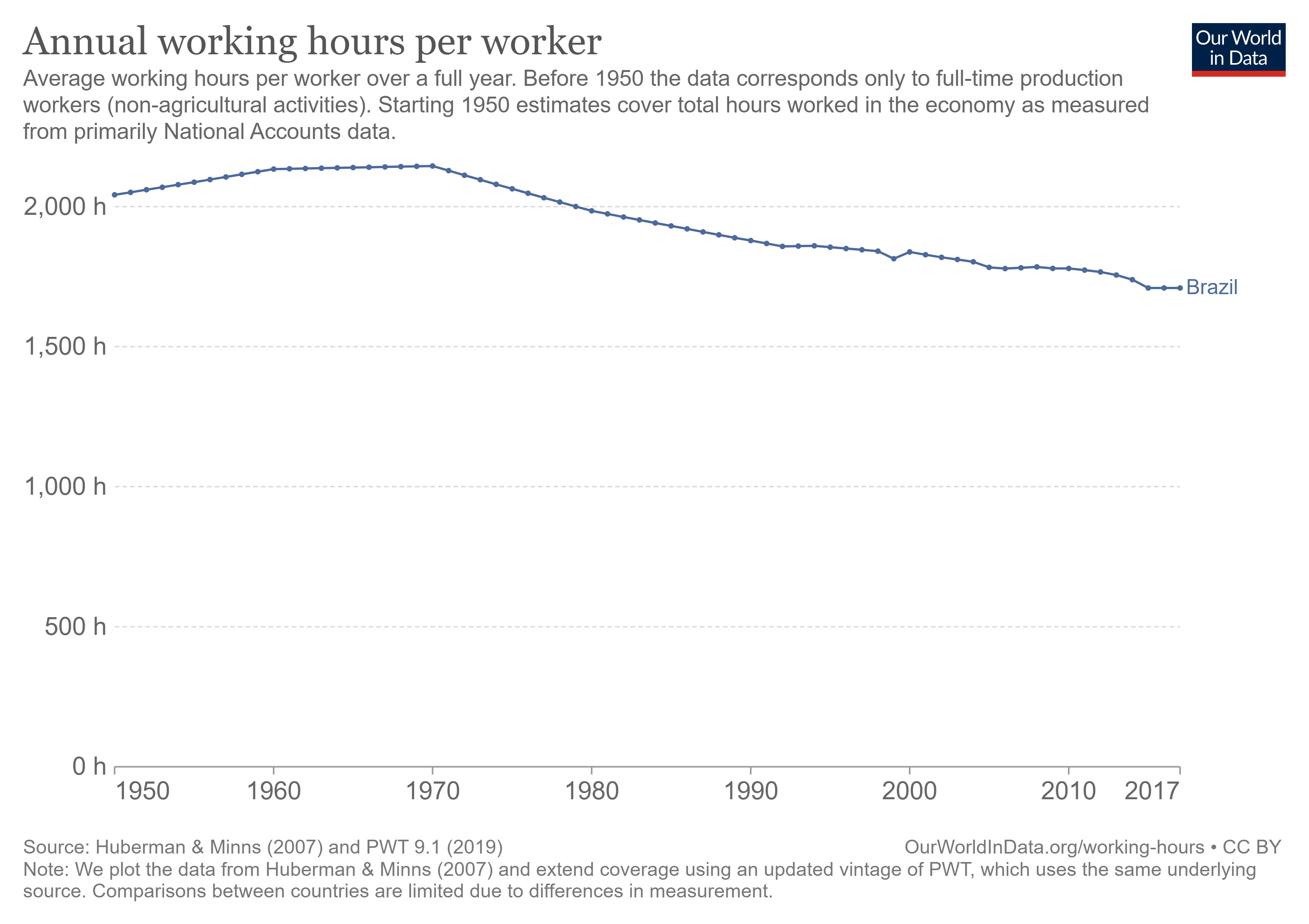

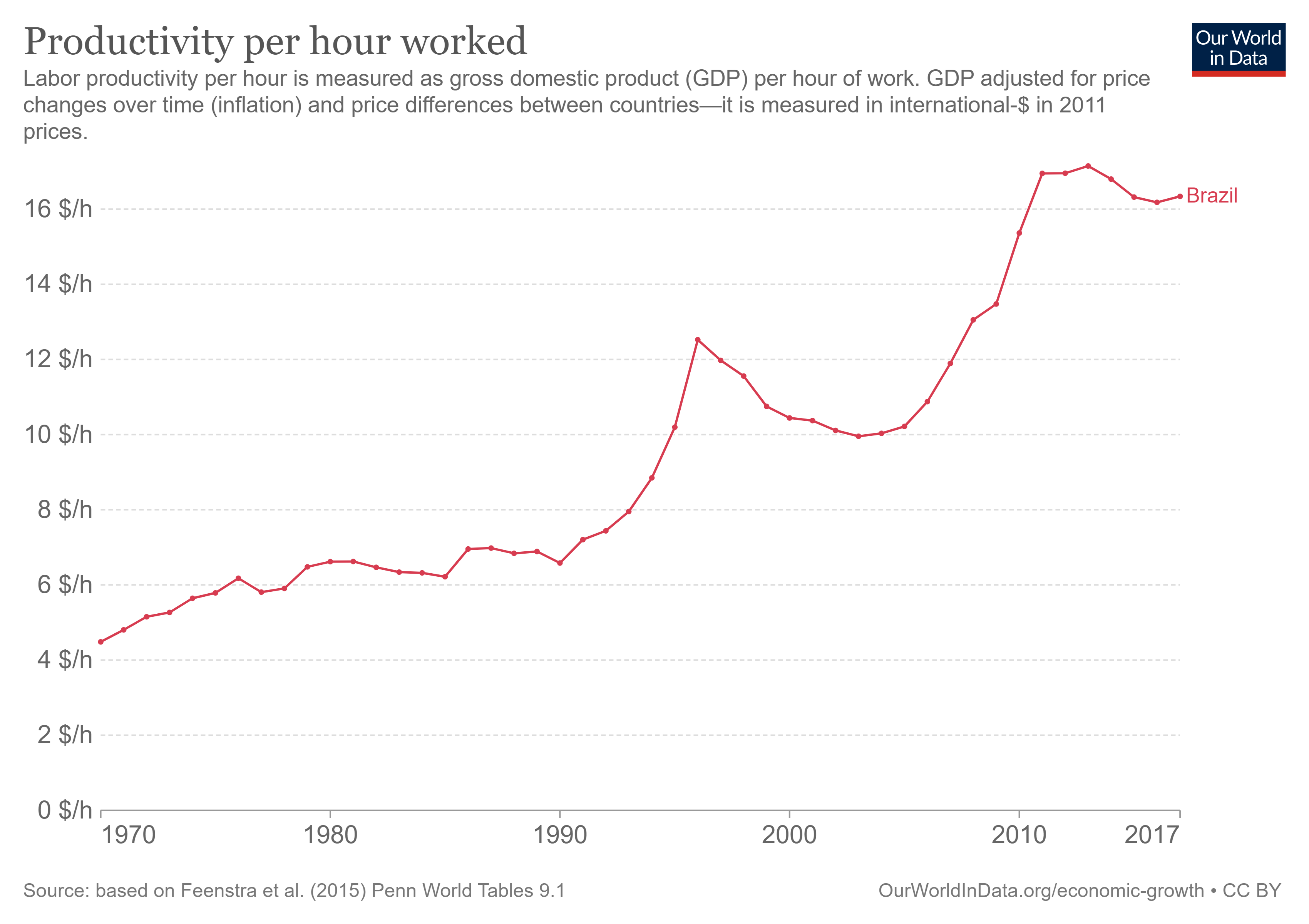

In general, according to visualisations prepared by Our World in Data:

A country’s GDP per capita is inversely proportional to the number of hours worked. In other words, people in richer countries work less. For example, in 1990, workers in Brazil worked an average of 1,879 hours per year. As the country has developed economically, this number has fallen, with Brazilian workers putting in only 1,709 hours/year (33 hours/week) in 2017.

A country’s productivity is also inversely proportional to the annual number of hours put in by its workers. Again, using Brazil as an example: in 1970, each worker worked an average of 2,145 hours/year while the country’s productivity (GDP per hour worked) was a meagre USD 4.49 (2017 terms). In 2017, workers worked only 1,709 hours but their productivity was equivalent to USD 16.34.

You Might Also Want To Read: Important financial considerations for studying abroad

Final Thoughts

The length of the average working week (and year) varies depending on one country to another. While workers in some countries are burning the midnight oil, others enjoy excellent work-life balance. A number of factors determine the extent of these disparities. They also determine why these disparities exist in the first place.

In general, workers in rich, developed nations tend to have shorter working hours. They also enjoy other perks such as guaranteed annual leave, maternity/paternity leave and of course, better working conditions.

By contrast, workers in low and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa and the Americas work longer hours and suffer from lower pay, greater job insecurity (greater unemployment rates), ‘working poverty’ (poverty despite regular employment) and fewer guaranteed leaves.

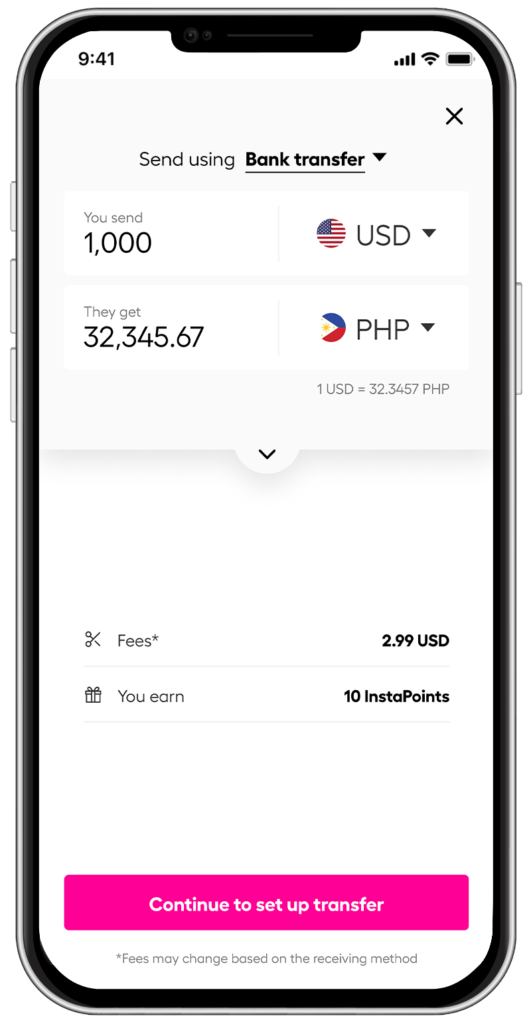

Sending money overseas?

Let Instarem be a part of your journey. Here’s why:

*rates are for display purposes only.

Cost-effective

Low transfer fees enable you to send money to multiple destinations without burning a hole in your pocket.

Easy and fast

Transferring money to other countries is typically an instant transaction.

Trusted and secure

Regulated by nine financial regulators across the globe with, licenses in Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, India, the UK, the US, the EU, and Canada.

Earn loyalty points

Get loyalty points for every transaction and referral you make. You then redeem your points as discounts for future transactions.

Transparency

Absolutely no hidden costs. You will be in the know of the exact rates and fees applied to your money transfer.

Send money overseas with Instarem for your next transfer.

Download the app or sign up on the web and see how easy it is to send money with Instarem.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only. All details are accurate at the time of publishing. Instarem has no affiliation or relationship with the products or vendors mentioned.

Instarem stands at the forefront of international money transfer services, facilitating fast and secure transactions for both individuals and businesses. Our platform offers competitive exchange rates for popular currency pairs like USD to INR, SGD to INR, and AUD to INR. If you're looking to send money to India or transfer funds to any of 60+ global destinations, Instarem makes it easy for you. We are dedicated to simplifying cross-border payments, providing cutting-edge technology that support individuals and businesses alike in overcoming traditional fiscal barriers normally associated with banks. As a trusted and regulated brand under the umbrella of the Fintech Unicorn Nium Pte. Ltd., and its international subsidiaries, Instarem is your go-to for reliable global financial exchanges. Learn more about Instarem.